Features is an in-depth series about the records, songs, or even shops, labels and other pieces of the musical ecology. Pieces of vinyl, CDs or online bits of music hanging around in digital corners. It includes the pieces that had previously been classed as oddfinds. From my point of view, an oddfind is good - very good, but I was never totally happy with the moniker!

If you like this post, let me know, or even better let someone else know! And if you’re intrigued about what’s coming down the line, hit subscribe and you’ll get each episode by email as it’s published (unless you’ve already subscribed, in which case, I thank you!).

Features #4.1: Beth Gibbons: a triptych, Part 1

For those who know and love Beth Gibbons, her work is not an oddfind at all. But it's worth saying that outside of her band, Portishead, she has only released three records over three decades – all of them intriguing, unexpected and courageous. The three Portishead album were themselves all adventurous, seminal offerings in the times in which they landed. So what might be considered ‘odd’ is the sparsity of her output, juxtaposed with its variety and undoubted excellence.

What inspired this piece was the release of Beth Gibbons’ first official solo album, Lives Outgrown, on May 17th 2024. I spent much of that day listening to the album on a loop and I love it already. As I write this, reviews are already hailing the album with four and five stars.

However, it’s really Beth’s voice that is the oddfind. From the first bars of Glory Box (first track on Dummy) to the last strains of Whispering Love (the final track on the new album), the music and arrangements have always swirled around the unique qualities of her voice.

Specifically, this piece is dedicated to and inspired by the three albums – a 22-year triptych – that Beth Gibbons has released outside of Portishead. These are listed below (in order of my discovering them rather than release). This first post covers the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs and parts two and three (next week) will reflect on Out Of Season and Lives Outgrown – sister albums separated by 22 years:

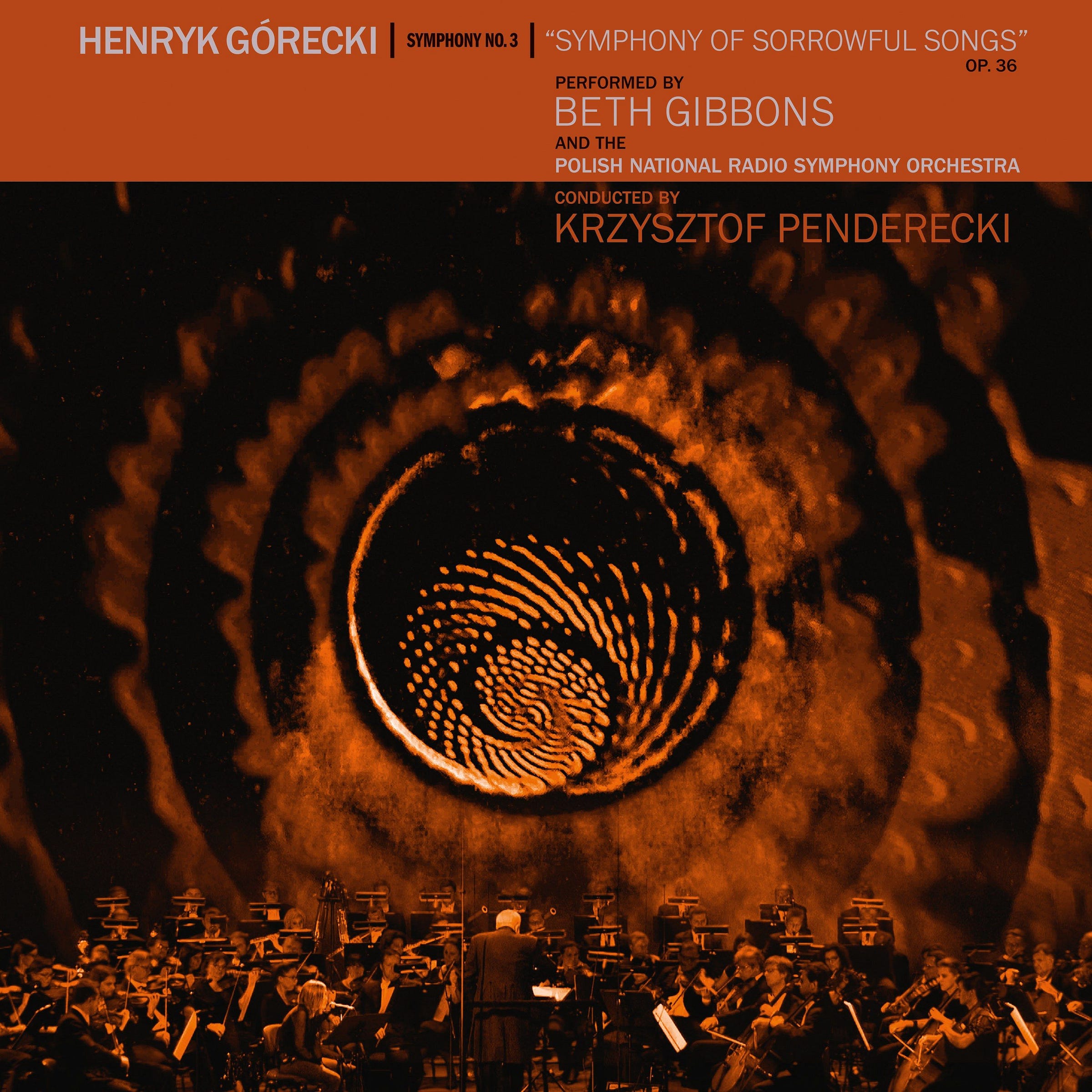

Henryk Gorecki Symphony No 3, Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, OP 36. Performed by Beth Gibbons and the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, and conducted by Krzysztof Penderecki, released in 2014.

Out of Season by Beth Gibbons & Rustin Man (aka Paul Webb) released in 2002, probably the direct forerunner of Lives Outgrown in musical terms.

Lives Outgrown by Beth Gibbons, released May 17th 2024.

Part 1. Symphony of Sorrowful Songs

For me, like many in the early 90s, Portishead were part of the soundtrack of those changing times. My CD collection tracks the post-punk, soul and hip-hop influences that led us to what then was called ‘trip-hop’ – Acid Jazz, Massive Attack’s Blue Lines; the sample heavy work of DJ Shadow; Coldcut; Bjork’s Debut and, of course, Portishead’s first album, Dummy – among many others. I loved the broken-down, soulful fusion of these records and the directions they were taking me.

There was also a brittle melancholy in much of this music. What separated Dummy from the others was Beth Gibbon’s voice that seemed to match this mood exactly. It often sounded unschooled – sometimes whispering, sometimes rasping, sometimes yearning. I loved that album – still do – and I’d never heard anyone sing like Beth Gibbons. As a person, she appeared enigmatic and down to earth, seemingly living for the music – but not caring much for the business itself.

Not long after their eponymous second album in 1997 – Portishead, the band, became history, and Beth Gibbons’ voice a fondly remembered, though iconic part of that mid-nineties era. I would occasionally drag out Dummy from the shelves and give it a play, but there was a lot of other music out there to listen to and admire.

It wasn’t until 2014 that I came across Beth Gibbons again. I’d somehow missed her 2002 Rustin Man collaboration (more on that in the next post), but had always kept my eye on oddfinds in the crossover worlds of classical, jazz, electronic and popular music. I always liked odd collaborations and left turns – Elvis Costello recording with the Brodsky Quartet; Ryan Adams re-recording the whole of Taylor Swift’s album, 1989; Drum and Bass acts appearing at international Jazz festivals; the Ninja Tunes crew and Cinematic Orchestra; Bjork working, and inviting remixes from anyone and with no boundaries at all – and so on.

Around the same time that trip-hop was coming onto the scene, there were waves of innovation happening in classical music too. Magazines like Classic CD and the BBC’s publication, Music, with CDs on their cover (paralleling publications like Uncut, Mixmag and Mojo in the pop, rock and dance music worlds) grew the audience for classical music, and encouraged labels to branch out and record music from composers and artists beyond the traditional ‘classics’. One of these was Henryk Gorecki, a relatively unknown Polish composer of avant-garde contemporary classical music in the late twentieth-century.

His third symphony written in 1976, Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, became famous when it was recorded by the London Symphionetta, conducted by David Zinman, and sung by the soprano, Dawn Upshaw. The 1992 release sold over a million copies, and I must have heard an extract on one of those cover CDs, because I remembered the strains of the second movement a little further down the line. As a result of that recording, Upshaw became a classical star: a regular voice on various song-cycles, oratorios and opera recordings – a number of these created specifically for her.

In 2014, a new live recorded version of the Symphony, sung by Beth Gibbons (in the Upshaw role) and conducted by Krzysztof Penderecki, was released by Domino. When I came across it, I was intrigued and excited. The story behind the recording speaks to Gibbons character, and also qualifies the album as a true oddfind! As a non-Polish speaker and untrained singer (though not an unrecognised one, as I’ve noted!), she was invited to work with the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra and decided to tackle the live performance and recording by learning the piece phonetically. She doesn’t (or didn’t) read music, so learning and performing the piece as Dawn Upshaw would have wasn’t an option either!

In spite of this, the record – and the live performance – is extraordinary. The piece is heartrending in its source – the song in the second movement is drawn from a prayer written on the walls of a Gestapo prison in 1944 by a young Polish woman imprisoned there, Helena Wanda Blazusiakówna:

No mother, do not weep. Most chaste Queen of Heaven Support me always. Hail Mary, full of grace.

We know the way that war in Europe went for millions of people, and so it’s not hard to imagine the terror that Helena must have been experiencing as she wrote these words. As the record’s sleeve notes tell us:

Beneath was a signature and the words “18 years old, imprisoned since 25 September 1944”.1

Gorecki’s later work draws on his Catholic faith and the folk history of his country. The other two ‘sorrowful songs’ Gorecki composed from on the Third Symphony are drawn from Polish folk and religious sources. The third movement’s words are particularly moving, speaking to stories of loss and upheaval that had persisted in Europe from long before the 20th Century’s horrors unfolded.

Where has he gone My dearest son? Perhaps during the uprising The cruel enemy killed him

Of course, these songs are sung in Polish and it was the intrigue of the project and Beth Gibbons’ special voice that drew me. However, the sentiments are universal. The political and spiritual contexts are tragic and familiar, and yet this English woman from Devon singing these songs in Polish somehow captured all that poignancy and grief. Somehow you know, as you do when listening to something like Shostakovich’s 8th String Quartet or Anohni in full flow, that you are hearing music that means something big – offering warnings and elegies, in the form of humanly composed sounds and voices, as perhaps only music can do – against the terrors and brutalities of oppression.

Beth Gibbons’ acceptance of such an ambitious project is something that few people would or could attempt. She’s not a classical singer – but her performance here, singing a full symphonic classical piece in a language that is not her own, is very special indeed – unique in its tone and quality.

While I was researching this post, I listened to Dawn Upshaw’s original recording of the Second Movement of the Sorrowful Songs alongside Beth Gibbons’ version. Upshaw is, as you’d expect, note perfect; her song building slowly up through the rich and beautiful playing of the Sinfionetta. It is finely judged and very moving, the strings sustaining a deep bass register in the piece for her voice to ascend through...

What makes Gibbons’ performance so great, however, is that she matches, even surpasses, this emotionality. Her voice is higher in the mix, and so its frailty is exposed – but the effect is that this perfectly matches the words and sentiments of song. Her voice isn’t perfect, but it’s utterly perfect for the performance. The piano audibly provides rhythm and accompaniment and she sits on a chair in amongst the strings, not so much as a soloist, more like a first violist. Or maybe, as she was in Portishead, just part of the band…

The full playlist on Youtube is HERE and a version of the full film of the whole performance is below. It’s well worth an hour of your time!!! Or pick up the record, download or CD from HERE.

Parts 2 and 3 of this piece, ‘Beth Gibbons: a triptych’, will follow next week…

Notes

I was pleased to discover that Helena survived that Gestapo prison. According to Wikipedia: “Eight weeks after her capture, on 22 November 1944, Błażusiakówna was being transported by the Nazis by train, and was one of 12 people rescued by guerrillas. She walked over the mountains to Nowy Targ, where she was given a skirt and a large scarf. That evening she was back with her grandparents in Szczawnica. She fell ill and spent the rest of the war in hospital, where the staff took great risks to treat her and hide her identity.” She was part of the Gorals or Highlander ethnic group in the Poland/Slovakia border area and had been captured by the Nazis as part of their ethnicification of the Polish minorities. She survived the war, had five children and died in 1999 aged 73.